Learning foreign languages affects music processing in brain

Published : 03 Aug 2021, 00:22

Updated : 03 Aug 2021, 00:24

A music-related hobby boosts language skills and affects the processing of speech in the brain, according to a new research study.

The study also said that the reverse also happens – learning foreign languages can affect the processing of music in the brain, said the University of Helsinki in a press release on Monday, quoting the study.

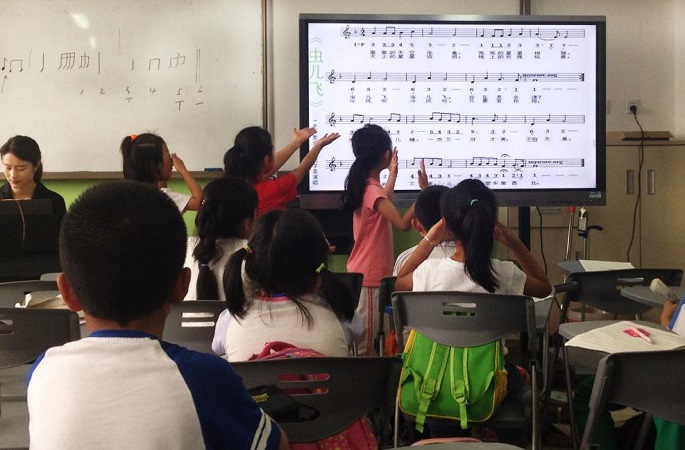

Research Director Mari Tervaniemi from the University of Helsinki’s Faculty of Educational Sciences investigated, in cooperation with researchers from the Beijing Normal University (BNU) and the University of Turku, the link in the brain between language acquisition and music processing in Chinese elementary school pupils aged 8–11 by monitoring, for one school year, children who attended a music training programme and a similar programme for the English language.

Brain responses associated with auditory processing were measured in the children before and after the programmes. Tervaniemi compared the results to those of children who attended other training programmes.

“The results demonstrated that both the music and the language programme had an impact on the neural processing of auditory signals,” Tervaniemi said.

Surprisingly, attendance in the English training programme enhanced the processing of musically relevant sounds, particularly in terms of pitch processing.

“A possible explanation for the finding is the language background of the children, as understanding Chinese, which is a tonal language, is largely based on the perception of pitch, which potentially equipped the study subjects with the ability to utilise precisely that trait when learning new things. That’s why attending the language training programme facilitated the early neural auditory processes more than the musical training,” Tervaniemi added.

Tervaniemi said that the results support the notion that musical and linguistic brain functions are closely linked in the developing brain. Both music and language acquisition modulate auditory perception. However, whether they produce similar or different results in the developing brain of school-age children has not been systematically investigated in prior studies.

At the beginning of the training programmes, the number of children studied using electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings was 120, of whom more than 80 also took part in EEG recordings a year later, after the programme.

In the music training, the children had the opportunity to sing a lot: they were taught to sing from both hand signs and sheet music. The language training programme emphasised the combination of spoken and written English, that is, simultaneous learning. At the same time, the English language employs an orthography that is different from Chinese.

The one-hour programme sessions were held twice a week after school on school premises throughout the school year, with roughly 20 children and two teachers attending at a time.

“In both programmes the children liked the content of the lessons which was very interactive and had many means to support communication between the children and the teacher” said Professor Sha Tao who led the study in Beijing.